Vanuatu's Victory – International Law Requires States to Act Against Climate Change

On 23 July 2025, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) issued its groundbreaking Advisory Opinion, no. 187 (Advisory Opinion), in which it for the first time specified the obligations of States under international law in respect of climate change. According to the ICJ, failing to act against climate change may constitute ‘an internationally wrongful act’ for States under international law. Although the ICJ's Advisory Opinions are not legally binding judgments, they carry significant authority in interpreting States’ obligations under international law.

In this article, we outline the main takeaways of the Advisory Opinion and discuss its impact on companies.

Background

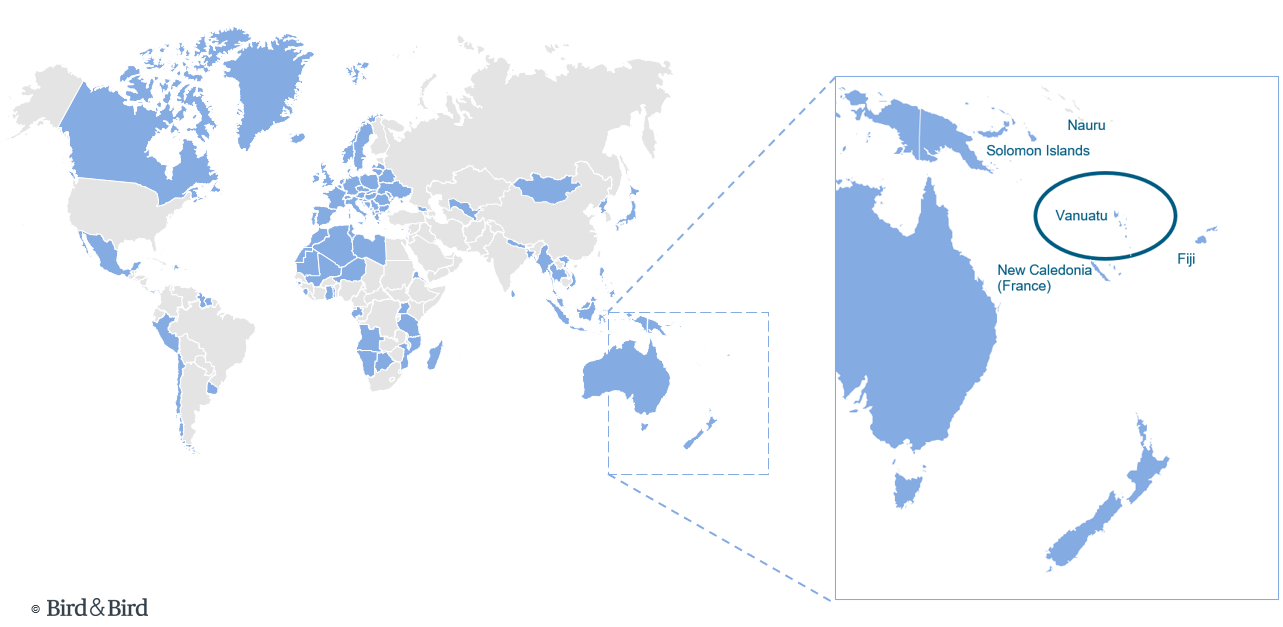

Vanuatu is a small island state in the Pacific. Like many other small island nations in the Pacific, Vanuatu is faced with the severe consequences of climate change, ranking first on the 2021 UN University World Risk Index and losing a third of its entire GDP due to cyclones in the past.

Vanuatu, together with a core group of 17 other nations, led an initiative to request an Advisory Opinion from the ICJ, which was co-supported by 132 nations. Following the adoption of Resolution A/RES/77/276 by the UN General Assembly on 29 March 2023, the ICJ was requested in accordance with Article 96 of the UN Charter to render an Advisory Opinion pursuant to Article 65 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice.

In short, the ICJ was asked to answer the following questions:

- What are States’ legal obligations under international law to address climate change and protect current and future generations? and

- What legal consequences arise if they fail to fulfil these duties, resulting in significant climate harm?

States Obligations – Voluntary or Binding?

UN climate treaties

First of all, the ICJ emphasised that the UN climate treaties (i.e. the UNFCCC, the Paris Agreement, and the Kyoto Protocol) include legally binding obligations in accordance with the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties and customary international law. Furthermore, the ICJ expressed that the international climate treaties are not incompatible with each other, but mutually supportive.

Secondly, although the Paris Agreement refers to keeping the global average temperature rise below the 2.0°C above pre-industrial levels and as an additional effort pursues to keep the global average temperature rise below 1,5°C, the ICJ considered that the 1.5°C threshold has become the scientifically based consensus target and the new primary target that the parties subsequent agreed upon.

Thirdly, the ICJ also notes that the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities” is enshrined in the Paris Agreement but adds that it should be applied “in the light of different national circumstances” – meaning a country’s status (i.e. a developed or developing country) can change over time. This principle guides how countries implement the Paris Agreement. In short, developed countries must also help developing countries with money, technology, and training, showing a duty to cooperate.

As fourth point, the ICJ elaborates on the consequence in case climate treaties impose an obligation of conduct and in case they impose an obligation of result. An obligation of conduct requires a state to use all available means to achieve a goal; failure to do so is wrongful, even if the goal isn’t reached. A result-based obligation requires actually achieving the specified outcome. For example, in climate policy, simply adopting policies isn’t enough—the policies and measures must be capable of meeting the set goal, not just exist in form.

Obligations under other environmental treaties and human rights law

The ICJ also found that States have binding obligations to protect the climate system, stemming from other environmental treaties and human rights law. Regarding environmental treaties (for example, the Ozone Layer Convention, the Montreal Protocol, the Convention on Biological Diversity, and the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification), the ICJ points out that the obligations in those treaties also complement the obligations set out in the UN climate treaties. Hence, international environmental obligations also ensure the protection of the climate system as a whole, particularly in the field of atmospheric preservation, biodiversity protection, and desertification prevention.

With regard to human rights law, the ICJ decided, in particular, that these treaties form part of the most relevant applicable law to determine States’ obligations with regard to climate change. In that regard, the ICJ also refers to regional developments, such as the judgment ‘KlimaSeniorinnen/Switzerland’ by the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) and the recent Advisory Opinion 32/25 by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (AICHR).

The ICJ considers that the protection of the environment is a precondition for the enjoyment of human rights. Therefore, the ICJ ruled: “[T]he human right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment is essential for the enjoyment of other human rights." Although the ICJ does not refer to specific national cases, its reasoning on climate change in relation to human rights law is similar to the reasoning set out in major national climate cases, such as the Dutch Urgenda-case, the judgment of the Indian Supreme Court, and ruling by the South Korea’s constitutional court.

The ICJ recognizes climate migrants and also holds that States cannot send back these migrants based on the principle of non-refoulement as climate change infringes human rights.

Customary international law

In addition, ICJ clarified that the duty that lies upon States to address climate change not only follows from the UN climate treaties, human rights law or international environmental law treaties, but also from customary international law. According to the ICJ:

Climate change is a common concern. Co-operation is not a matter of choice for States but a pressing need and a legal obligation.”

This is important as customary international law also applies to States that are not part of any climate treaty (as well as to those that have withdrawn from such treaties or intend to do so).

Attributing State Responsibility and possible Compensation

The ICJ’s Advisory Opinion provides that failing to take measures may constitute an internationally wrongful act attributable to the State. Put differently, climate inaction by governments can be seen as a breach of international law (including customary international law). In contrast to the Written Statement by the European Union, the Advisory Opinion clearly states that States may be liable in case they breach these obligations.

Regarding the causation of harm, the ICJ held that harm caused by multiple concurrent factors does not absolve a state from its duty to make reparations. Particularly, since the ICJ refers to the scientific opportunities to determine individual GHG emissions and countries’ share of GHG emissions. Moreover, while it may be difficult and must be assessed on a case-by-case basis, the ICJ does not regard the identification of a causal link automatically to be impossible in the context of climate change. According to the ICJ, these matters must be assessed on a case-by-case basis to determine whether the causal link between the wrongful act and the injury suffered is established. This opens a window of opportunity for claimants.

Future generations

Interestingly, the ICJ’s Advisory Opinion also clarifies the obligations of States towards future generations in relation to climate change. According to the ICJ: “the environment is not an abstraction but represents the living space, the quality of life and the very health of human beings, including generations unborn.”

Consequently, states must observe the interests of future generations – albeit within certain legal boundaries – as a matter of common sense (i.e. intergenerational equity). Moreover, the ICJ points out that the UN climate treaties also incorporate the concept of intergenerational equity and that this principle, therefore, must be taken into account when interpreting those treaties.

Consequences

The ICJ Advisory Opinion is considered groundbreaking, as it affirms that States have binding obligations with respect to reducing GHG emissions, regardless of whether they have committed to do so in climate treaties. Moreover, States guilty of causing an internationally wrongful act have a duty of cessation of the act and must guarantee non-repetition. In addition, States may be held accountable to pay damages in case they breach these obligations to the injured state. Individuals may also invoke States’ responsibility under international human rights law and ask for reparations.

Furthermore, regarding the payment of damages, it is noteworthy that States retain their statehood even if their territory would disappear or its inhabitants are permanently replaced in case of sea level rise. This way, the ICJ aims to solve a potential future threat as sea level rise would affect the State’s territorial integrity and sovereignty over their natural resources, which, by extension, affect the right to self-determination.

Relevance for private parties?

While international law, strictly speaking, applies, in principle, to States, the ICJ’s Advisory Opinion may also be relevant for companies.

Firstly, obligations imposed on States may ultimately lead to policies and legislation that also affect private parties. Particularly, since the ICJ refers to the role States in taking appropriate protection measures against GHG emissions that explicitly relate to:

fossil fuel production, fossil fuel consumption, the granting of fossil fuel exploration licences or the provision of fossil fuel subsidies”.

In other words, States can be held accountable for the actions/omissions of private actors (companies) under their jurisdiction. Consequently, decisions by States that fail to address climate change or even contribute to climate change targeted at the private sector, such as issuing licences and investments, may be challenged before courts.

Secondly, it has long been acknowledged under international law that companies have a role to play in addressing climate change and protecting human rights. Particularly, because the causes of (anthropogenic) climate change are not only caused by States, but also by companies. The responsibility of companies to prevent climate change and respect human rights is also enshrined within international soft law instruments, such as the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGP) and Chapter VI of the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct 2023 (OECD Guidelines). Moreover, national judges may rule under national tort law — through the courts' interpretation of open norms, — that private parties have a duty to take action against climate change, which could be based on international (soft) law and human rights treaties. For example, from both the Dutch appeal case Shell/Milieudefensie of 12 November 2024 and the German case of Luciano Lliuya/RWE AG by the Oberlandesgericht Hamm of 28 May 2025 (i.e. the case of the ‘Peruvian farmer’), can be derived that companies have a duty of care to prevent climate change.

Thirdly, no matter the actual action taken by States in light of the ICJ’s Advisory Opinion, the effects of climate change and other sustainability issues, whose adverse effects could intensify over time, may impact your business activities in the long-term.

Other actors, like NGOs, employees, investors, consumers or governmental authorities, could also require more action from companies to address the adverse impact of climate change and thus affect your business. For example, the municipality of The Hague banned fossil fuel advertisements such as promoting cheap flying tickets and luxurious cruise holidays, in its public areas. This ban was upheld in court as it was deemed a necessary measure to address climate change (read here our analysis of this judgment).

Addressing sustainability issues and climate change, therefore, requires action from States, but also from companies. At Bird & Bird, we are committed to helping you achieve your ESG ambitions by navigating your organisation through the vast maze of regulatory obligations or by advising your organisation to ensure that it will become a leader that is prepared for the future – in the interest of future generations.