Decrypting India's New Data Protection Law: Key Insights and Lessons Learned

On August 11th 2023, the Indian Government enacted the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 (“DPDP Act” or “the Act”) by publishing it in the Official Gazette. The DPDP Act, when effective (as per dates to be notified), will govern the personal data processing activities of a broad range of organisations that operate in the Indian market.

To align with global standards, the DPDP Act has been partially modelled off Regulation (EU) 2016/679 (“the GDPR”), and data protection laws of Singapore and Australia. The DPDP Act will replace the current data protection laws encapsulated under the Information Technology Act (“IT Act”) and the Information Technology (Reasonable Security Practices and Procedures and Sensitive Personal Data or Information) Rules 2011 (“SPDI Rules”).

The law does not contain an explicit transition or grace period for compliance. In light of the inaugural round of discussions concerning the implementation of the DPDP Act by the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (“MEITY”) on September 20th, 2023, a graded approach for compliance with the DPDP Act with transition timelines may be possible.

The structure of this article is as follows: we provide an analysis of the law below and explore the key similarities and differences to the GDPR, we then explain with reference to the DPDP Act its scope and covered actors, processing obligations, data subject rights, transparency and accountability requirements, cross-border data transfers, and enforcement and liability.

Key Takeaways from a GDPR Point of View

| Similarities to GDPR | Differences to GDPR |

| The DPDP Act applies to personal data processing in India where such data is in digital form or is in non-digital form and is digitized subsequently. It will also apply to processing outside of India if the processing is in connection with any activity related to the offering of goods or services in India. |

Unlike the GDPR which has both an establishment (Article 3(1) of the GDPR) or targeting criterion (Article 3(2) of the GDPR) for its territorial scope, certain provisions of the DPDP Act do not apply to processors in India that process personal data of individuals outside of India pursuant to any contract entered into with companies also located outside of India (e.g., in outsourcing arrangements). |

| The DPDP Act covers “data fiduciaries” and “data processors” (which overlap with the concepts of data controller and data processor in the GDPR, respectively). A written agreement must be struck between data fiduciaries and data processors. However, the data fiduciaries remain responsible for complying with the provisions of the Act. |

A category of organisations that the Central Government designates as “significant data fiduciaries” will carry heightened obligations (including appointing a data protection officer (DPO) in India and conducting periodic data protection impact assessments (DPIA), audits, etc). |

| Data fiduciaries must have a lawful purpose of processing and adhere to other processing principles. Some conditions that permit lawful processing in the DPDP Act mirror the legal bases under the GDPR. |

Consent must always be collected except in circumstances where there is a “legitimate use” of the data, one of which relates to employment purposes. However, certain legal bases provided for in the GDPR, are not included in the DPDP Act such as contractual necessity and legitimate interests. |

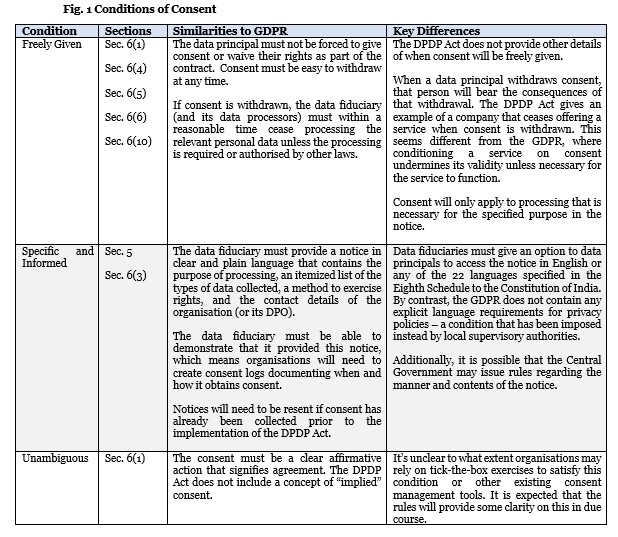

| When obtaining consent from individuals, data fiduciaries must ensure it is free, specific, informed, unconditional and unambiguous with a clear affirmative action. A privacy notice describing details such as the purpose of processing and the types of data collected must be presented. |

Unlike the GDPR, the DPDP Act does not contain a section on special categories of personal data nor seems to require data fiduciaries to publish privacy policies (as is the case with Articles 13 & 14 of the GDPR) in general situations. There are certain obligations under other sectoral laws. |

| The DPDP Act grants rights to individuals including the right to access, correction, erasure, nominating individuals and seeking grievance redressal. |

Unlike the GDPR, the DPDP Act does not contain a right to data portability or a right not to be subject to automated decision making with legal or significantly similar effect. Access rights may be limited to scenarios. |

| The DPDP Act imposes special safeguards around the processing of children’s data. |

Before processing any personal data of children or persons with disabilities (with lawful guardians), data fiduciaries must obtain verifiable parental consent of the parent (or such lawful guardian). The manner of obtaining such verifiable parental consent will be prescribed through rules under the Act. A child is anyone under the age of 18, unless designated otherwise by the Government. |

| Data fiduciaries must adopt technical and organisational measures to ensure security of data. In case of a personal data breach, the Data Protection Board of India (“DPBI”) and the affected data subjects have to be informed. Other data breach notification rules will be subsequently promulgated by the Government. |

Unlike the GDPR, which mandates a representative is appointed in writing where an organisation is caught by Article 3(2) of the GDPR’s extraterritorial scope, data fiduciaries on the other hand, do not have to appoint a representative. However, data fiduciaries are required to appoint a point of contact and significant data fiduciaries are required to appoint a DPO respectively for the purpose of grievance redressal. Significant data fiduciaries are also required to conduct a DPIA, undertake periodic audits, etc. |

| The DPBI will enforce the DPDP Act and can issue enforcement orders and financial penalties for violations. This is the new Indian data protection supervisory authority. |

Unlike the GDPR, which mandates that transfers of personal data to third countries or international organisations may only take place in defined circumstances and in compliance with Chapter V of the GDPR, the DPDP Act by default permits the transfers of data across borders. However, the Indian Government may establish possible transfer conditions in future and designate certain countries to which data transfers are prohibited. Also, cross border data transfers will be subject to any higher degree of protection or restrictions under any other laws in India. The Central Government may through notification exempt its agencies from the provisions under the Act, inter alia in the interests of state security and maintaining public order. Such exemption could extend to the conditions for processing personal data, as well as the applicable data protection principles, such as collection, purpose and storage limitation requirements under the Act. |

1. Material Scope, Extraterritoriality, and Covered Organisations

Section 3 of the DPDP Act sets forth the scope of the law, which applies to the processing of personal data both within and outside the territory of India if certain conditions are met.

- Processing Within India – Companies located in India will fall in scope where they process within India any digital personal data or non-digital personal data which is digitized subsequently. Note, the applicability of the DPDP Act does not turn on whether an entity is “established” in India.

- Processing Outside of India – Additionally, the DPDP Act applies extraterritorially if companies process personal data outside India but in connection with any activity related to offering goods or services to individuals located in India (Sec. 3(b)). It is unclear if this would also involve monitoring behaviour, as a provision including a reference to this was dropped in the final version of the law.

In addition to these scoping provisions, Section 3 includes a household exemption when data processing occurs for solely personal or domestic purposes. The Act will similarly not cover personal data made publicly available by the data subject or under law (Sec. 3(c)).

Covered organisations – data fiduciaries and data processors

The DPDP Act applies to the processing activities of data fiduciaries. Like the concept of controller in the GDPR, a data fiduciary refers to any person who alone or in conjunction with other persons determines the purpose and means of processing of personal data (Sec. 2(i)). The Central Government of India may designate a special class of these entities as significant data fiduciaries, based on factors such as the volume and sensitivity of data processed and the risk of harm. These entities must comply with heightened obligations (see below). It is expected that big tech companies may be designated under this category.

A data processor is any person who processes personal data on behalf of a data fiduciary (Sec. 2(k)). The DPDP Act does not contain many terms (or a separate section) that uniquely apply to data processors. For instance, while there is an equivalent provision to Article 28 of the GDPR that requires data fiduciaries to enter into a data processing agreement (DPA) with their processors, the DPDP Act does not prescribe any minimum necessary terms. In addition, processors in India processing data of foreign individuals on behalf of or pursuant to a contract with a company also outside of India will be exempted from certain provisions of the Act (Sec. 17(1)). This is different from the GDPR, under which processors located in the EEA would still fall within the scope of the GDPR in application of its Article 3(1), regardless of whether or not they process personal data on behalf of organisations located outside of the EEA.

2. Covered Data and Processing Obligations – Data Protection Principles and Lawful Processing

The DPDP Act governs the processing of personal data of data principals, which are the individuals to whom the personal data relates. The concepts of personal data and processing seem to overlap textually with those in the GDPR: personal data is that which relates to an “identified or identifiable individual” while processing includes typical operations such as collection, structuring, storage, sharing, disclosure by transmission, destruction etc. While the DPDP Act offers some illustrative examples of processing activities, it remains unknown how the text will apply in practice.

With respect to data principals, this term is for the most part the same as data subjects under the GDPR, but also extends to parents or lawful guardians of children or a person with disability (Sec. 2 (j)).

Data protection principles

Chapter 2 of the DPDP Act establishes the obligations of data fiduciaries, including the circumstances where they may process personal data. Although the DPDP Act does not expressly refer to data protection principles, the Citizens’ Data Security and Privacy Report submitted to the Lok Sabha (i.e. Lower House of the Parliament of India) on August 1st 2023, that outlines the Act’s legislative history and key considerations, explains their explicit connection to the requirements of the law and their similarity to internationally recognised standards. For instance, the law includes provisions that govern:

- Legality and Transparency – Every person that processes personal data must do so in accordance with the law, have a lawful purpose, and meet transparency requirements when collecting consent (Sec. 4 and 6).

- Purpose Limitation – Data fiduciaries must specify a purpose of processing and describe the personal data involved in the processing (Sec. 5(1)). When relying on consent, the processing must only be necessary to achieve the stated purpose (Sec. 6(1)).

- Accuracy and Completion – Section 8(3) requires data fiduciaries to ensure the personal data they process is accurate, complete and consistent.

- Security and Integrity – Data fiduciaries must implement appropriate technical and organisational measures and take reasonable security safeguards to prevent unauthorised disclosures (Sec. 8(4-5)).

- Storage Limitation – The Act also requires data fiduciaries (except for state bodies) to cease retention and delete personal data as soon as the purpose for which the data was collected has been achieved, and if the retention is no longer necessary pursuant to any legal obligation (Sec. 8(7)). These conditions may be limited by other factors, such as where the data principal approaches the data fiduciary for the performance of a specified purpose, or to exercise any of her rights (Sec. 8(8)).

Lawful purpose – a strong reliance on consent and “certain legitimate uses”

Like the GDPR, the DPDP Act requires data fiduciaries to have a lawful purpose for all processing operations. By contrast, it does not list separate lawful grounds from which an organisation can choose (such as in Article 6 of the GDPR). Rather, data fiduciaries must primarily obtain consent and can in some circumstances rely on “legitimate use” conditions.

Consent – Section 6 of the DPDP Act sets forth rules on consent, which significantly change existing requirements for data fiduciaries. Currently, the SPDI Rules require organisations to obtain consent in writing when they collect “sensitive personal data” which includes an exhaustive list of data types. The DPDP Act extends this requirement to all personal data and imposes a more stringent standard for consent using a ‘clear affirmative action’, that seems to be partially modelled off the GDPR.

Legitimate Uses – As mentioned above, data fiduciaries may rely on certain legitimate uses to process personal data under limited circumstances, when obtaining consent to lawfully process personal data may be practically infeasible. These nine alternative grounds are defined as certain legitimate uses, under Section 7 of the Act. While some of these grounds overlap with the lawful grounds to process personal data under the GDPR, certain grounds are unique to the Indian context.

- For instance, there are provisions recognising grounds for processing personal data, such as performing a legal function (only for state bodies), compliance with an order or obligation issued under law (i.e., legal obligation) and protecting the life of individuals (i.e., vital interests). There are also conditions in relation responding to medical and public emergencies such as epidemics, disasters, and breakdowns in public order.

- Among the unique grounds are circumstances when data principals voluntarily provide personal data to the data fiduciary for a specified purpose and to which there is no indication by the data principal that consent for such purpose has not been given. Further, to facilitate HR and payroll administration, as well as employee monitoring and supervision, the DPDP Act allows data fiduciaries to process personal data for employment purposes, and to safeguard employers from loss or liability. While the employment related purposes are not exhaustively defined, indicatively, these could include preventing corporate espionage, maintaining confidentiality of trade secrets, intellectual property and classified information as well as providing any service or benefit to data principals that are employees. This ground may not be applicable in the context of independent contractors or consultants.

- The DPDP Act currently does not include conditions covering contractual necessity or legitimate interests. A previous version of the DPDP Act (a bill at that time) contained an exemption for processing in the public interest, but this has since been modified to only apply to state bodies.

Exemptions – Section 17 exempts data fiduciaries from most obligations under the Act in specific situations including when processing is (i) necessary to enforce legal rights and claims, (ii) conducted by courts or tribunals in the connection of a judicial function, and/or (iii) in the interest of prevention, detection, investigation, and prosecution of any offence under law. Notably, the Act does not apply to processing of personal data by government agencies notified by the Central or State Government (on certain grounds such as when in the interest of Indian sovereignty and security). Further, the Central Government may exempt processing that is necessary for research, archiving, and statistical purposes from the scope of the Act, provided that (i) such processing is not used to make decisions about a specific data principal, and (ii) is carried out in accordance with the standards prescribed by the Central Government. The Central Government may also exempt certain data fiduciaries (including start-ups) from certain provisions of the law considering the nature and volume of personal data processed.

3. Heightened Processing Situations - Children’s Privacy, Significant Data Fiduciaries, and No Special Category Data

The DPDP Act sets forth additional processing requirements for special circumstances. Like the GDPR, there is a recognition in the law that these conditions require heightened care due to the enhanced risks they carry. The DPDP Act notably does not contain provisions seen in other global data protection laws such as a section on special category data or automated decision-making (ADM).

- Children’s Privacy and Parental Consent - Section 9 of the DPDP Act imposes additional obligations for data processing related to a child, which strictly refers to any individual under the age of 18 (Sec. 2(f)). The DPDP Act indicates that the Government will set future rules to clarify the scope of these requirements. These include:

- A requirement to obtain verifiable parental consent (VPC) or that of a lawful guardian before processing children’s data (Sec. 9(1)). This means that such individuals’ age must always be verified.

- Restrictions on processing that are likely to cause detriment to a child (Sec. 9(2)).

- A prohibition on tracking, behavioural monitoring, and targeted advertising to children (Sec. 9(3)).

- The Central Government may lower the age criteria from 18 years, if satisfied that a data fiduciary has ensured that its processing of personal data of children is done in a manner that is verifiably safe, resulting in exemption of the data fiduciary from some of the abovementioned obligations. (Sec. 9(5)).

- Duties of Significant Data Fiduciaries – The Central Government may notify classes of data fiduciaries, considering factors such as the volume and sensitivity of the personal data processed, risk to the rights of data principals, and their impact on state security and sovereignty and integrity of India, as significant data fiduciaries. These entities must appoint a DPO that is based in India to act as the point of contact for complaints and grievances. This person must be responsible to the Board of Directors of the entity or a similar governing body. Significant data fiduciaries must also appoint an independent auditor to evaluate compliance on a periodic basis and undertake a data protection impact assessment (Sec. 10(2)).

- Special Category Data - The DPDP Act does not contain any provisions on special category data. Under the SPDI Rules (which will be repealed once the DPDP Act comes into force), sensitive personal data includes passwords, financial information, medical and health data, sexual orientation, and biometrics (i.e., technologies that measure and analyse human body characteristics for authentication purposes). Organisations processing this data are subject to enhanced rules including an explicit requirement to obtain consent (although this standard is significantly lower than what the DPDP Act requires).

4. Data Subject Rights and Duties

Like other data protection laws, the DPDP Act identifies rights of the data principal, but uniquely obligates these individuals to also adhere to certain requirements when exercising them (and even imposes monetary penalties on individuals that violate these requirements). These include not registering false or frivolous grievances, impersonating other data principals, and/or providing false identity materials (Sec. 15). Notably, the section on data subject rights only applies to data fiduciaries and not their processors – although this obligation may flow down via contractual arrangements.

| Rights Included | Description |

| Right to Access |

Data principals may obtain confirmation of whether the data fiduciary processes their personal data, a summary of the data being processed, the processing activities involved, and, the identities of all data fiduciaries and processors that have received the data and the categories of data shared, subject to certain exemptions. Note, like under the GDPR, this right can be actioned with regards data fiduciaries only. |

| Right to Correction |

Data principals may request data fiduciaries to correct, complete, and update any inaccurate or misleading personal data (for which, the data principal has previously given consent, or has voluntarily provided such data for a specified purpose) they process. State bodies may be exempt from this provision if certain conditions are met (Sec. 17(4)). |

| Right to Erasure |

Upon request, a data fiduciary must erase the personal data of a data principal that is no longer necessary for the purpose for which it was processed unless the retention is necessary under law or the purpose for which it was processed has not expired. State bodies may be exempt from this provision if certain conditions are met (Sec. 17(4)). It is unclear if this right to erasure includes a right to be forgotten, as it seems expressly conditional on the purpose of processing expiring. |

| Right to Grievance Redressal |

Data principals may register a complaint with a data fiduciary for any processing activity related to their personal data. If the data principal is not satisfied with the response, that individual may register a complaint with the DPBI. |

| Right to Nominate |

Data principals may also nominate another individual who, in the event of death or incapacity of the data principal, shall exercise that principal’s rights. |

| Rights Excluded |

Description |

| Right to Data Portability |

The DPDP Act does not set forth a right to data portability or discuss transferring data held by one data fiduciary to another. |

| Right Not to be Subject to automated decision-making |

The DPDP Act does not include provisions regarding the scope and applicability of automated decision-making with legal or significantly similar effects. |

The DPDP Act explicitly recognises that the Central Government may exempt certain data fiduciaries from the requirement to respond to an access request (Section 17(3)) as well as certain other obligations.

5. Transparency, Accountability, and Security Measures

In addition to lawfulness of processing, the DPDP Act imposes other obligations on data fiduciaries including accountability measures and security requirements.

Transparency Disclosures and Privacy Policies – While data fiduciaries must present a privacy notice to individuals when they collect their consent, the DPDP Act does not contain an equivalent to GDPR Articles 13 and 14 that require general disclosures for transparency purposes. The content and manner of providing such privacy notices under the DPDP Act may be further clarified by the Central Government in due course. Data fiduciaries must give an option to data principals to access the consent notice in English or any of the 22 languages specified in the Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution.

Accountability Requirements – Data fiduciaries are responsible for the processing activities of their processors and must take steps to ensure accountability including publishing the contact details of its DPO (if considered a significant data fiduciary) or a person who is able to answer data protection related questions. These organisations must also establish a grievance redressal mechanism for data principals to make complaints (Sec. 8(10)).

Compared with the GDPR, the DPDP Act does not require other accountability obligations such as:

- Maintaining a record of processing activities (ROPA);

- Maintaining a log of security breaches;

- Conducting a DPIA for high-risk processing (except significant data fiduciaries that are required to carry out DPIAs periodically); and

- Appointing a representative as under the GDPR (other than a point of contact for data fiduciaries and a DPO for significant data fiduciaries)

- Registering with the supervisory authority.

Like with other sections of the law, these requirements may be expanded and clarified by subsequent rules and guidance.

Data Breaches and Technical and Organisational Measures – Data fiduciaries and data processors must implement appropriate technical and organisational measures, although the specifics of these remain undetermined in the law and will be addressed in subsequent rules. In the event of a personal data breach, Section 8(6) requires companies to notify the DPBI and every affected data principal in a manner that will be prescribed by future rules. It is currently unclear how these requirements will compare with the GDPR and other data protection laws around the world. The DPDP Act defines a personal data breach as any unauthorised processing or accidental disclosure, acquisition, sharing, use, alteration, destruction, or loss of personal data that compromises confidentiality, integrity, or availability of personal data (Section 2(u)). While the definition seems to resemble that of the GDPR, it does not contain a concept of risk of harm for determining reportability thresholds. As stated above, this may be clarified in future rules.

6. Cross-Border Data Transfers

Chapter 4 of the Act governs the transfer of personal data outside of India. It specifies that a data fiduciary may transfer personal data for processing to any country or territory outside India except to countries to which it the Central Government may restrict transfers by notification. The Central Government may through notification set forth conditions for the transfer of personal data, including restrictions to certain destinations such as restrictions on data transfers to neighbouring countries owing to geopolitical considerations. Compared with previous iterations of the DPDP Act at bill stage, which imposed localisation requirements for certain categories of critical personal data, the DPDP Act significantly relaxes data transfer obligations. Notably Section 16(2) clarifies that the DPDP Act will not supersede existing transfer restriction requirements operating in India under different sectoral laws or administrative regulations (e.g., RBI rules).

7. Enforcement and Liability

Finally, the DPDP Act calls for the creation of the DPBI to inquire into complaints, oversee compliance with the Act, and issue administrative sanctions including corrective orders and monetary penalties.

- Investigations and Enforcement – The DPBI has the power, on receipt of a complaint from a data principal or reference from a government authority, to initiate a proceeding (and in the instance of a data breach issue remedial directions). The DPBI must determine whether there are sufficient grounds to proceed with an inquiry before launching an investigation. The DPBI’s powers are broad and include requesting information and company records, summoning parties, and requiring assistance from law enforcement. The DPBI may also issue interim orders during its investigation, close inquiries, and even sanction complainants if it finds the complaint frivolous. Appeals from decisions of the DPBI will be handled by the Telecom Disputes Settlement Authority of India, an appellate tribunal, from which further appeal may lie before the Supreme Court, India’s apex judicial body.

- Voluntary Undertakings – Data fiduciaries may voluntarily undertake compliance with the DPBI and promise to take a specified action within a specified time or refrain from certain processing activities. If the DPBI accepts such an undertaking, any proceedings concerning the contents of the undertaking would be barred, unless the data fiduciaries fail to comply with such undertaking or breaches its terms.

- Financial Penalties – Organisations found to be non-compliant with the DPDP Act may be subject to a financial penalty. The Schedule of the DPDP Act sets forth a penalty structure for violations of certain sections, which range from 50 crore (£5 million) to 250 crore (£25 million). Note the DPDP Act does not contain an equivalent provision regarding a percentage of global annual turnover like the GDPR.

The authors thank Khaitan & Co for their insights and contribution to this article.